From: “Sindbis virus polyarthritis outbreak signalled by virus prevalence in the mosquito vectors”, J.O. Lundström, J.C. Hesson, M.L. Schäfer, Ö. Östman, T. Semmler, M. Bekaert, M. Weidmann, Å. Lundkvist and M. Pfeffer (2019), PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007702

Sindbus virus (SINV) is a virus found across the world. Usually, it is transmitted between birds such as Fieldfare and Redwing (both of which are winter visitors to the UK) by mosquitoes. However, it sometimes makes the jump to humans (zoonosis) where it produces a disease characterised by joint pain and rashes, known variously as Pogosta disease (in Finland), Ockelbo disease (in Sweden) and Karelian Fever (in Russia).* Interestingly, it appears that SINV is mainly transmitted between birds by two almost indistinguishable species of mosquito Culex torrentium and Culex pipiens, but usually transmitted to humans by another species, Aedes cinereus. It has been suggested that SINV outbreaks occur on a seven-year cycle, but it is not easy to be sure, as records in humans seem to be fairly heavily influenced by how much interest governments were taking in the disease at the time. If outbreaks could be accurately predicted, the public could be forewarned to take protective measures. Even simple measures like using insect repellent and wearing more covering clothing could save doctors a lot of time and money, and patients a lot of pain.

Jan Lundström’s team had a theory. They tested thousands of mosquitoes caught in light traps around eight lakes in central Sweden every other week from 2001 to 2003 for the presence of SINV, suspecting that an outbreak in mosquitoes may precede an outbreak in humans.** They were also able to take genetic samples of the virus, in order to determine its outbreak history.

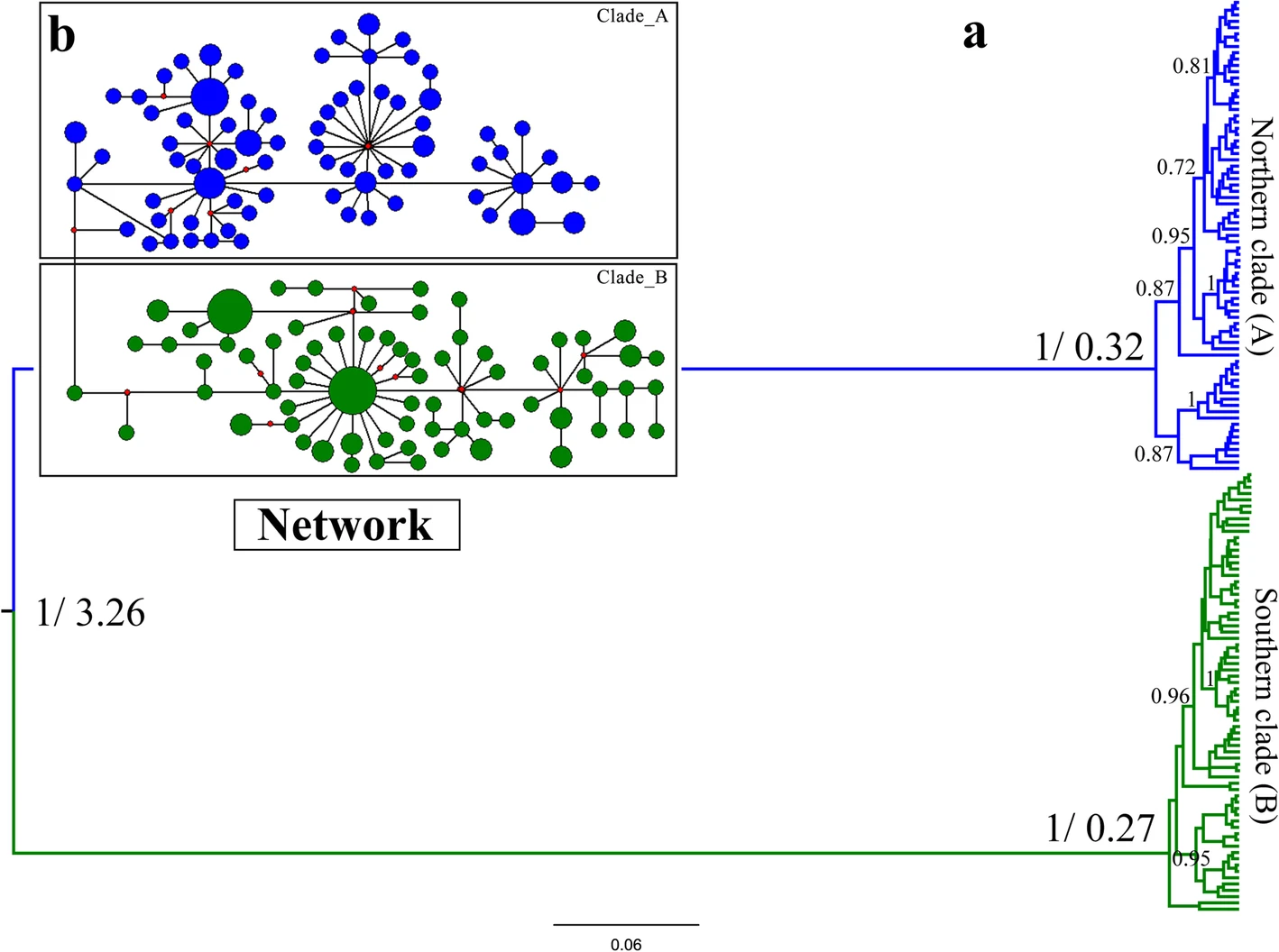

What they found was surprising. It seems that SINV is fairly new to Scandinavia, having arrived only a century or so ago, and slowly emerging into significance in the late 1960s and 70s. What’s more, it appears to have, somehow, arrived four separate times. The scientists don’t speculate on how this could have happened, but further research may yet turn up some very interesting finds.

The authors, reasonably, focus a lot more on how and when SINV turns up in their mosquitoes, both Aedes and Culex. On the basis of the seven-year theory, they thought that 2002 would be an outbreak year, and, happily, it was found that only a small proportion of mosquitoes in 2001 were infected, rising sharply in 2002 and then declining again in 2003. Intriguingly, all the 2001 virus samples were found in Culex mosquitoes, but it then appeared in Aedes cinereus in 2002, allowing it to make the jump to humans, and was only found in Aedes in 2003. This might not mean anything, but it does hint at the possibility that SINV has to reach a certain prevalence in birds before Aedes cinereus will pick it up and transmit it to humans. When the scientists looked at mosquitoes in 2009, seven years after 2002, they again found an increase in the prevalence of SINV, suggesting that spikes in the number of mosquitoes infected with SINV coincide with outbreaks in humans. Which makes perfect sense, when the mosquitoes are the things transmitting the virus.

It has been noticed before that in Sweden, SINV cases appear in front of doctors from July to October, most commonly in mid to late August. The researchers found that the mosquitoes followed the same pattern. This study detected SINV in mosquitoes between the 30th July and the 10th September, and a previous one found a slightly earlier, but very similar time period of the 16th July to the 30th August. Not only does this give Swedes a timeframe to be particularly wary of mosquito bites, it also gives researchers looking for SINV in mosquitoes a tighter window, with less time wasted looking for the virus when it is less likely to be around. This means that it will be a lot easier to properly test the seven-year outbreak theory, using mosquitoes as a more reliable record of how prevalent SINV is. Human medical records are great, but you can’t assume that every person infected is going to show up to a doctor’s surgery or that no records have been lost. It could be that many more people than we think get infected, but never become ill enough to seek treatment. With mosquitoes, you can have a good stab and finding out exactly what percentage of the population has the virus, and track that fairly easily and accurately over time, with a far simpler database, and far fewer other factors to worry about. Mosquitoes live much simpler lives than we do – you don’t have to worry about whether their diet or exercise habits are skewing your data. The authors also suggest an effort to sample mosquitoes in early July could pay off in giving doctors a warning signal of when SINV cases in humans are likely to appear, and the public a warning of when to be careful. This, again, would save a lot of time and trouble.

It seems that it’s still early days for research into Sindbis virus, but I for one look forward to seeing how well the seven-year theory stands up to further testing.

*For more information on Sindbus virus see the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control here: https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/sindbis-fever/facts

** I don’t know why this is only getting published nearly 20 years later, but this sort of thing does happen in science sometimes, for all kinds of reasons

If you find any inaccuracy or lack of clarity in this article, please don’t hesitate to contact me on j.d.r1612@gmail.com and I’ll fix it as soon as I am able