From: “Persistence of multiple patterns and intraspecific polymorphism in multi-species Müllerian communities of net-winged beetles”, M. Bocek, D. Kusy, M. Motyka and L. Bocak (2019). Frontiers in Zoology 16:38

https://frontiersinzoology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12983-019-0335-8

We’ve all seen warning colouration – the stripes on bees and wasps, the bright hues of snakes and the colourful spots of tropical frogs all serve a single purpose, and that purpose is to send out a message to predators saying ‘don’t even bother trying to eat me’. The principle of aposematism – warning colours – entered western science in 1867, when Alfred Russel Wallace was grappling with why so many caterpillars have bright colours. He reasoned that some caterpillars must be distasteful to birds, but this in itself would not protect a caterpillar from being attacked if the bird didn’t immediately recognise that the caterpillar was no good to eat. The bird would need a signal it could easily spot, as even a slight injury to the caterpillar could be either fatal or very costly. He therefore suggested that the purpose of the bright colours of many caterpillars was to send a clear signal to birds not to eat them.*

Much further work in this area was done by Henry Walter Bates (who was present at the 1867 meeting where Wallace outlined his theory) and Fritz Müller, both of whom outlined important consequences of warning colours. Bates noticed that if a toxic or distasteful species lived alongside perfectly harmless ones, the harmless ones would often evolve to look like the dangerous ones. The famous example is in North American snakes – several harmless snakes resemble venomous species – but probably the most interesting example to look up is clearwing moths, many of which have an uncanny resemblance to wasps. As predators learn to recognise the markings of dangerous animals, they will assume that anything with similar markings is also dangerous, so harmless species gain protection from looking like dangerous ones. This is known as Batesian Mimicry, and it’s why hoverflies look like wasps.**

But the sort of warning colouration mimicry that Müller discovered, and Matej Bocek’s team were looking into, is just as interesting. Like most researchers looking into aposematism and mimicry, Müller studied tropical butterflies. He noticed that the toxic butterflies he studied all had very similar patterns – they mimicked each other, as well as being mimicked by harmless species. This makes perfect sense: if, for the sake of example, one toxic species has a bold red stripe across the forewing then predators will avoid anything with that stripe. So if another toxic butterfly has that stripe, it stands an advantage, as it will have a much lower chance of being eaten by predators that haven’t learned that red stripe=not tasty. The more toxic individuals across many species look like each other, the less chance they have of being eaten by a predator who hasn’t yet learned to avoid them. This is Müllerian Mimicry, and it’s why so many different species of wasps and bees all have black, yellow and orange stripes.

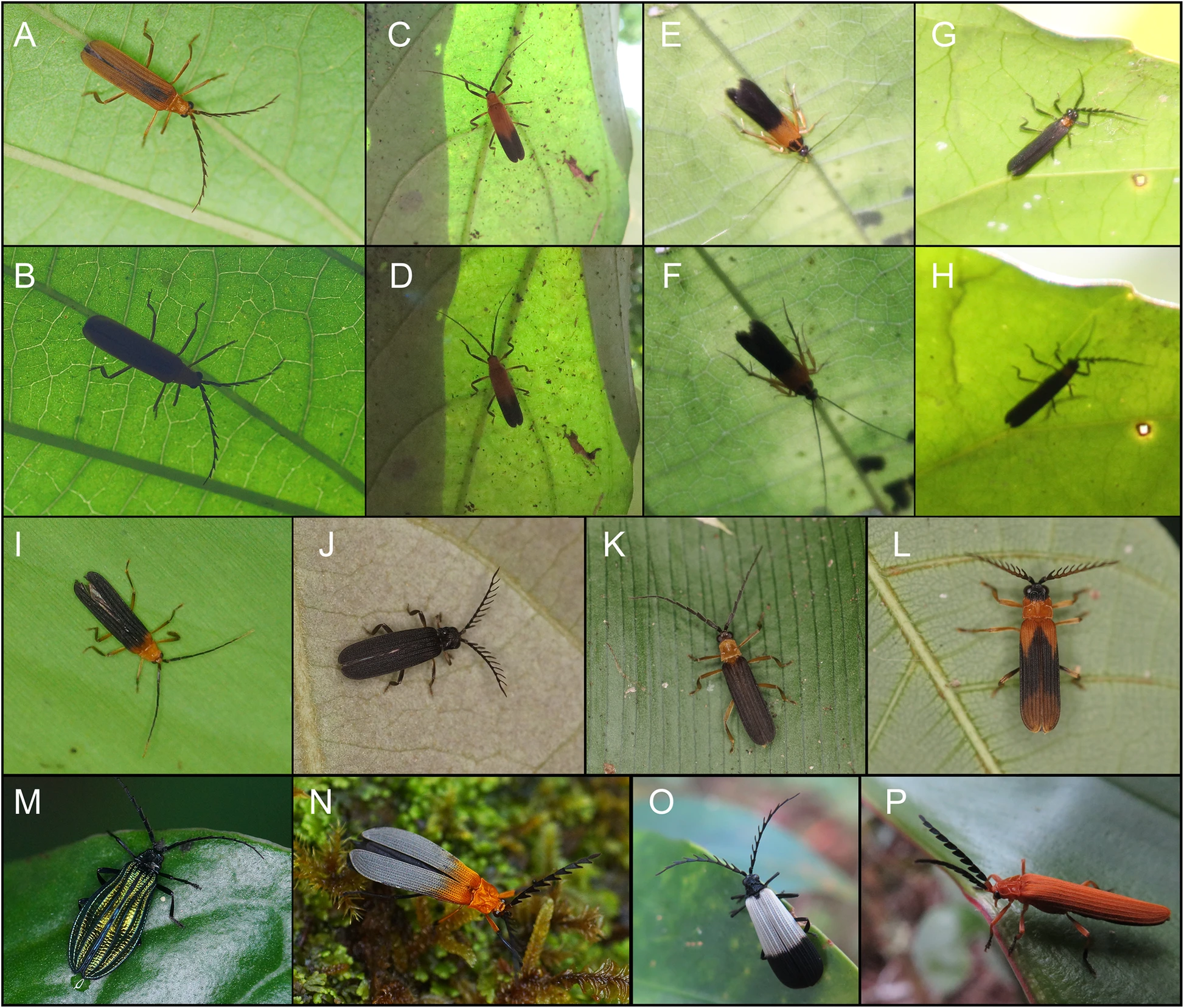

As I mentioned, most of the work in this area has been done on butterflies. Bocek’s team therefore decided to look at Müllerian Mimicry in a much more overlooked group of net-winged beetles, the genus Eniclases. Eniclases are known to be ‘unprofitable’ prey for predators, and have previously been shown to have their bright red, black, orange and yellow colours for warning, but have not otherwise been studied very much. The researchers collected 1,914 individual beetles from across New Guinea, catalogued their patterns, and took mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA – the sort that you only inherit from your mother) samples to work out how closely related the different species of Eniclases were.

They found that Eniclases species which looked very similar, and had similar patterns, were often not all that closely related, and that the more closely related species quite often had different patterns from each other. This is a pretty strong indication that Eniclases are Müllerian mimics: why would closely related species evolve in different directions and both end up looking like other, equally distasteful, species if not to take advantage of the protection offered by Müllerian Mimicry? Intriguingly, this doesn’t stop at species level – several species come in different colour forms, which resemble only very distantly related species. Presumably this means that the species can live in a greater variety of areas – it will be protected by its colours in any place where any one of its ‘co-mimics’ live.

The scientists also raise another interesting possibility: what if warning signals, and Müllerian Mimicry, aren’t confined only to colour? They noticed that Eniclases beetles like to sit on the underside of leaves, where their colour won’t be obvious to a bird or other predator looking at them from above – but their shape will be. The researchers speculated that this might be one reason why Eniclases species are all basically the same shape; if the shape of a toxic beetle is recognisable to predators, it would be advantageous to keep that shape. Even more tantalisingly, they suggest that this could explain why many mimics aren’t quite as similar in colour as they might be. If shape is also important, perhaps a beetle could get away with not having exactly the same colours as a toxic beetle the predator has already encountered because it is the same shape. Maybe the bird recognises a toxic shape as well as a toxic pattern, allowing beetles with imperfect mimicking patterns to escape.

More research is, as ever, needed, but this is a very intriguing suggestion. I’m looking forward to seeing how well this theory stands up to experiment.

* March 4th 1867, “Proceedings for the Year 1867”, Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society 15:7. Apologies for the historical detour, this is an area I did some research in a few years ago.

**More recent research has demonstrated that this only works if predators are more likely to encounter dangerous animals than harmless ones – otherwise they will learn to ignore the danger markings. There’s some great science about balancing selection across species and the population genetics of this phenomenon, which I would highly recommend looking into.

If you find an error or lack of clarity in this piece, please contact me on j.d.r1612@gmail.com and I’ll fix it as soon as I can.